San Francisco Chronicle Article by Peter Fimrite (1/3/09)

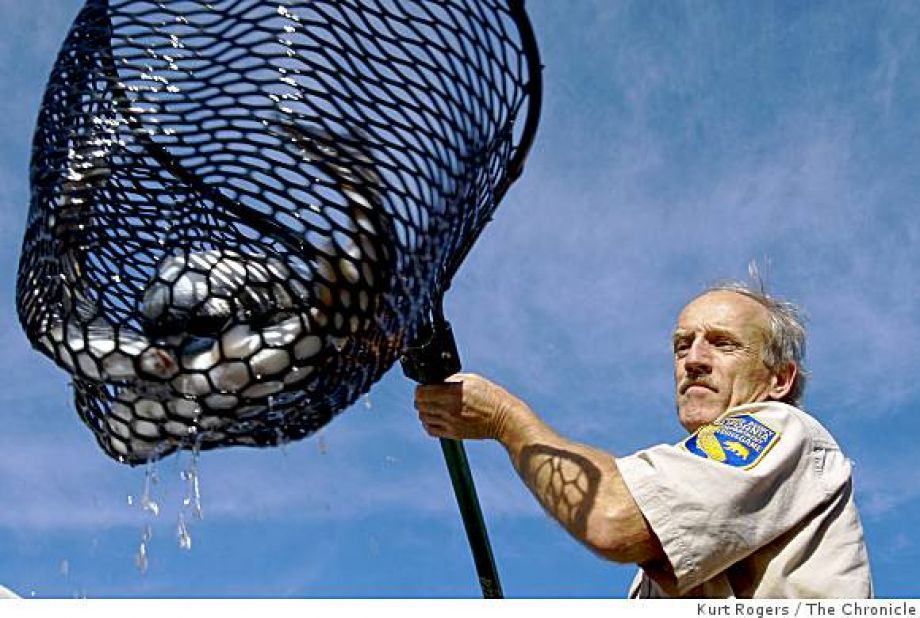

Manfred Kittel with the Department of Fish and Game nets Coho Salmon out of a tank on the back of a truck and hands the net to others to release into Salmon Creek on 12/11/08 in Bodega Bay, Calif

The nets that volunteers held in a remote river valley near Bodega Bay were full of the squiggling bluish fish that biologists hope will be the seed population of a new race of coho salmon.

The scaly, flapping critters were carried in nets from a truck 25 yards to the banks of Salmon Creek, a western Sonoma County tributary that winds through a stunning rural valley.

The 305 hatchery-raised coho were the first of their kind seen in any significant numbers in the degraded watershed since the mid-1970s, but their release last month was more than just a reintroduction.

It was part of a pioneering experiment in genetic diversity, the re-creation of a missing link that could serve as a bridge toward the renewal of this gravely endangered species.

“We are trying to develop fish with good strong genetic makeup that will lead to a durable natural population,” said Gail Seymour, an associate biologist and Salmon Creek watershed planner for the California Department of Fish and Game.

“We don’t know for sure that we are going to have full recovery by planting this minimal number of fish. It hasn’t been that long since we’ve known that diverse genetics are so critical.”

The fish that were released are a mix of 3-year-old coho from the Russian River and Olema Creek in Marin County. The combination may not seem like a big deal to most people, but the two populations are genetically unique, much like different races of people on different continents.

If they mate, as expected, the coho would repopulate the creek with an essentially new mixed race of salmon, a species of coho free from the debilitating problems that scientists are increasingly associating with hatchery inbreeding.

Creating a new race

Bob Coey, a senior biologist for the Department of Fish and Game, said the effort is part of a groundbreaking coho recovery effort that started in 2001 when the fish population in the Russian River hit bottom.

There were once an estimated 20,000 salmon fighting their way up the Russian River, but logging, gravel mining, overgrazing, vegetation removal, and huge amounts of sedimentation associated with residential and commercial development destroyed the fish habitat.

It is not an isolated problem. Coho, which are more sensitive to water temperature and quality than other salmonid species, have been dying off all along the West Coast. They were given additional protections in 2005 under the Endangered Species Act but things have gone downhill from there. Fisheries analysts reported a 73 percent decline in the already dismal number of coho returning to the creeks and tributaries along the coast of California during the 2007-08 spawning season.

Coho now make up about 1 percent of their historic population. The Russian River may be hit worst of all the big rivers. The coho population in the river dropped to about 100 in the late 1990s. Coey said fewer than 10 fish returned to spawn in 2001.

Capturing juveniles

The decline is why the Russian River Coho Broodstock Program was started by Fish and Game officials. They began capturing wild juvenile coho, raising them to adulthood in the hatchery, collecting their eggs after spawning and returning the offspring into the streams.

About 6,000 fish were released in 2004 and the numbers have grown ever since. About 90,000 juveniles a year are now released into the Russian River system, and experts say there are signs that things are beginning to improve.

But, as in any situation where you start with a limited population, in-breeding is a problem. In the wild, natural selection weeds out the weaker fish. In a hatchery, virtually all the fish survive and many of them turn out to be related to one another, according to biologists. As with humans, incest is not a recipe for strong genes.

“There hasn’t been enough genetic diversity, which means weaker strains develop,” Seymour said. “They are more susceptible to disease, they don’t have the ability to evade predators, they’re not as quick or strong and they may not be bright enough.”

That’s where the Salmon Creek watershed and the Marin County coho population come in.

Salmon Creek flows through a 35-square-mile watershed surrounded by about 200 ranches and farms into the town of Bodega and out to sea. It lost its coho largely because of livestock grazing and many of the same stressors that plague the Russian River. It is the last barren creek in the area, even though about $500,000 has been spent the past 10 years on watershed restoration.

It was chosen for the recovery plan because it is between the Russian River and Olema Creek, a western Marin County tributary that is part of the Lagunitas Creek watershed, home to the largest population of coho salmon in California.

Geneticists say they believe the historic population that existed in Salmon Creek before they disappeared was a genetic mix of Russian River and Lagunitas fish, so Fish and Game biologists decided to try to re-create that population using surplus hatchery fish. The 305 fish selected were genetically tested to ensure none of them was related.

“We’re trying to simulate the strain of salmon from two populations that occurred naturally in the past,” Coey said. “We’re releasing surplus adult Russian River and Marin County coho into the creek in the hope that these fish find each other and create a population on their own.”

Signs of hope

There is reason to believe it will work. Surplus hatchery fish have been released into Walker Creek, in West Marin, for the past five years. Coey said genetic testing has verified that those fish returned to the creek, which hadn’t seen coho for a couple of decades, and reproduced on their own.

The 2- to 3-foot-long adult coho struggled and splashed as they hit the water, then bolted out of the nets into the deep, free for the first time in their lives.

Ironically, their freedom will be short lived. They will spawn within the next month and die. Nobody will know how things worked out until their offspring return in three years to the place where they were born and lay their own eggs.

“This is really exciting,” Coey said, as the fish darted away up-stream, looking like underwater shadows. “Nobody has done this before.”

(Excerpted from: The San Francisco Chronicle)