Permaculture is a design process based in observation of natural processes and systems thinking that helps people create ecologically and socially sustainable ways of living in place. The word permaculture is a contraction of permanent agriculture and culture, as cultures cannot survive long without a sustainable agricultural base and land use ethic. We recognize and nurture the inextricable links between biological and cultural structures, from which truly resilient design solutions arise.

Why it Matters

How would our neighborhoods, towns, and cities look and feel if we were planning on thriving in place for the next 10,000 years?

Industrial society and its underlying neo-colonial, capitalistic drivers have created immense problems for most ecosystems in the world — from forests and grasslands to rivers and oceans — and for the people living in and around them who must breath, eat, drink and provide shelter for themselves. A privileged few hold disproportionate decision-making power, impacting the lives and wellbeing of huge numbers of people. Sustainable systems must challenge the current power structures and apply a radically ethical solutions-based approach to find our way. Problems can only be solved by significantly different ways of thinking that clearly identify false solutions that perpetuate exploitation. People with privilege are called to act as allies with impacted communities and act as leaders in their own. Thus, the ultimate goal of permaculture is not organic gardening, natural building, or renewable energy, but the cultivation and realization of new ways of seeing, thinking, and acting based on ethics and understanding of ecology.

OAEC’s work focuses on getting us away from a cradle-to-grave society to a circular economy based on ethical, ecological resource use.

Permaculture Ethics

- Earth Care – The prioritization of natural processes that support all life systems to cycle and regenerate.

- People Care – The right for all communities to engage with natural and cultural processes to ensure their well-being in a manner consistent with Earth Care.

- Fair Share – The governing of human needs and behaviors that results in the equitable availability of resources and rights for the Earth and all its inhabitants, including both the intrinsic rights and dignity due all people as well as the setting of limits to growth and consumption by those who are exhausting resources at an unjust and un-ecological rate.

Permaculture Principles

Design principles build upon ethics to inform and guide actions. These are generalized principles derived from the observation of natural patterns and the study of systems. Principles are meant to be conceptually universal, but the application of each will be specific to place, people, time, and context.

These are the permaculture principles that we use in our design process:

- Protracted and thoughtful observation (PATO) – Use lengthy and considered observation of natural systems rather than hasty and thoughtless labor.

- Stacking functions – Each element (noun, thing) performs many functions (verbs, needs).

- Planned redundancy – Critical functions are supported by many elements. For example, potable water is provided by roof-water catchment, a well, and a pond to unsure the availability at all times of the year for all needs on the site.

- Relative location – We can conserve time and energy through careful placement of elements in relation to each other and improve the functioning of the overall design. Everything has an effect on its environment on many scales. Every element in a design has an impact on other elements.

- Make the least change for the greatest possible effect – Make small strategic changes to save time, energy, resources and unintended consequences.

- Compose with rather than impose upon – Work with natural forces, processes, agencies and evolutions, so that we can assist rather than impede natural development. Use gravity to move water, use the sun to warm and light, use wind to cool, etc.

- Work from patterns to details – Work from a large scale down to a smaller scale while keeping in mind the larger scale at all times.

- Use on-site resources – Determine what resources are available and what resources are entering the system on their own and maximize their use. Waste is considered an unused resource.

- In the problem lies the solution – Often hidden in the problem is the solution we desire. Problems challenge our creativity and resourcefulness to devise workable, sustainable, and just solutions.

- Pollution is an unused resource – In natural systems, waste equals food. A design that results in a waste that cannot be the food for another organism or cycle is a bad design.

- Everything is connected – Everything has an effect on its environment on many scales. Every element in a design has an impact on other elements.

- Work in the dimension of time (aka succession of evolution) – Natural design follows a pattern of evolution based on dynamic equilibrium that optimizes stability and resiliency over time. Our own designs can follow suit and take advantage of change over time.

- Optimize yields – Increased cycling can increase yields. One gallon of water used to wash veggies, then to wash hands, then to water an orchard gives us the equivalent of three gallons of use.

- Think Spatially – Work in 3 dimensions. An ecosystem has multi-dimensional volume that exists and grows to the sides, up and down.

- Start small then expand – Implement in phases, being aware of scale and scope. Remember that every action causes a reaction. Build in time for feedback.

- It depends – Although principles can guide design, each solution must be specifically tailored to be appropriate for each given site in line with cultural and ecological uniqueness.

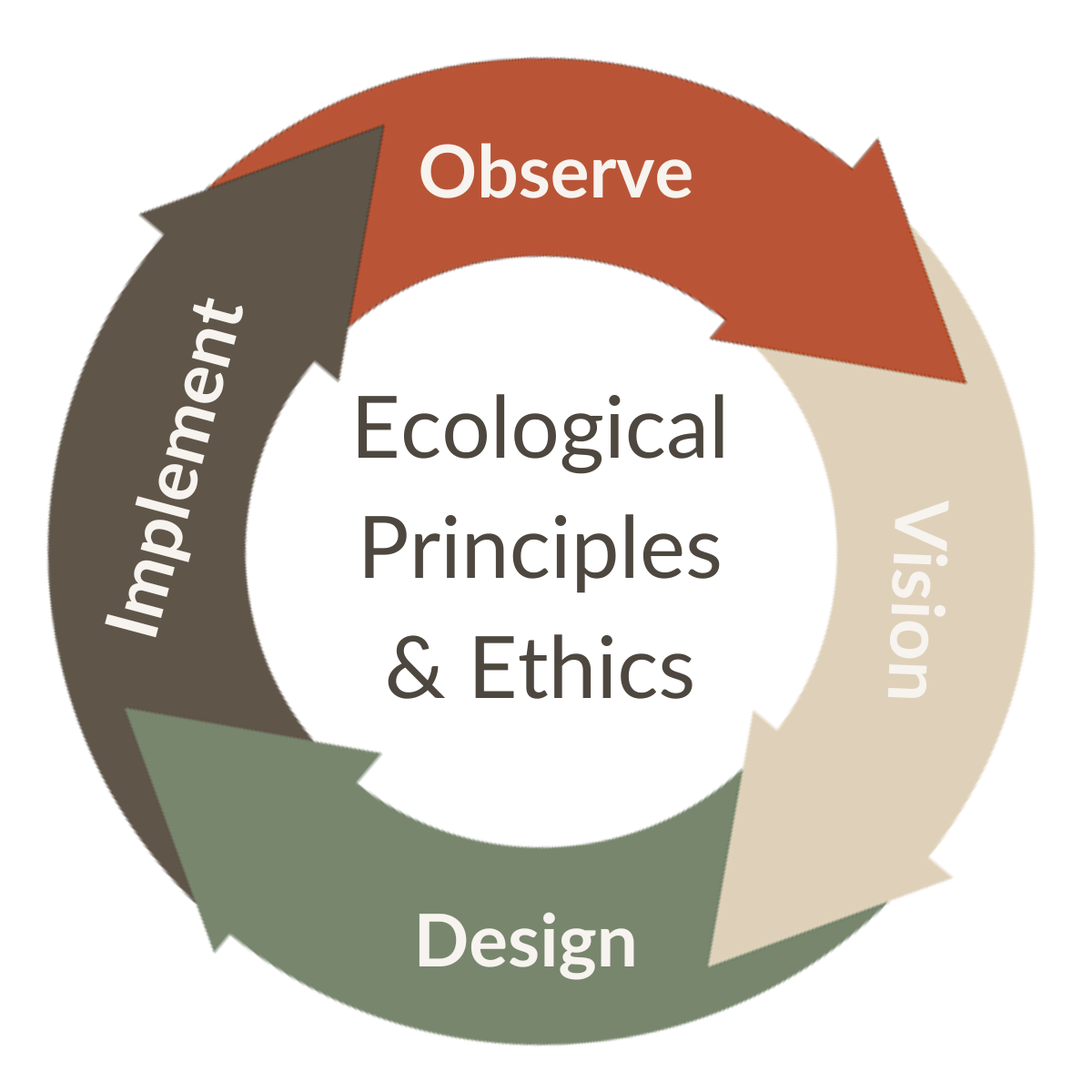

Phases of the Permaculture Design Process

The permaculture design process consists of four phases: assessment, visioning, designing, and implementation. The phases are based on natural systems thinking, ethical intention, and protracted and thoughtful observation.

- Observe – Observation guides and grounds design so it is reflective and responsive to place. The aim is to compose with rather than impose upon the powerful forces at play in natural systems and human communities. Design without assessment is not rooted in the land, but in human ego.

- Vision – Visioning, or goal setting, asks people to dream a future, state values, and develop a common statement for their work forward together. This step may be thought of as the assessment of the people involved in a project. In any project, it is a key step that if overlooked is detriment to the long-term project.

- Design – Design connects the vision with the observation. In the conceptual planning phase, design possibilities are creatively brainstormed based on the assessment findings, values, and goals – all inspired by natural systems thinking. Once possibilities are generated, these options are winnowed down using the principles as an ethical and functional sieve.

- Implement – Installation of the design often occurs in phases as the people, financial, and legal resources fall into place.

The design process is reiterative and may move linearly through design steps or may circle from one to another and back again. Depending on the information that arises in each phase, steps may be revisited and the design revised.

Permaculture Applied at OAEC

The 80-acre OAEC campus serves as a hands-on demonstration site for our Permaculture Design Certifications. This includes our biointensive Mother Garden and seed saving program, backcountry restoration of our Wildlands Preserve, the Conservation Hydrology demonstration site, long-term site development plan and intentional community.

Resilient Community Design

At OAEC, our approach to permaculture has evolved into a practice, a process, and a verb toward whole community well-being. We have applied our vision and strategy (focused on whole community capacity-building), social justice analysis, community organizing skills, ecological knowledge, and permaculture experience to create a design methodology that is meaningful and useable to place-based communities with widely differing backgrounds, experiences, knowledge, languages, and ages. Resilient community design is a facilitated process that enables groups to create designs to better address their social, cultural, ecological and economic needs, thus deepening their ecological understanding of their place and their ability to steward it.