Heating Water With The Sun

By Brock Dolman and Kate Lundquist

Photographs by Brock Dolman and Jim Coleman

Table of Contents

Resources

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Dean Witter Foundation, the Compton Foundation, and the Panta Rhea Foundation for their generous support of this project.

This report was compiled and written by Kate Lundquist and Brock Dolman, with input from Matt Every. Photographs by Brock Dolman and Jim Coleman.

OAEC’s WATER Institute was established to offer positive responses to the crisis of increasingly degraded water quality and diminishing water quantity. We promote a holistic and multidisciplinary understanding of healthy watersheds through our four interrelated program areas — Watershed Advocacy, Training, Education, and Research.

The Occidental Arts and Ecology Center (OAEC) is a nonprofit education and organizing center and organic farm in Northern California’s Sonoma County. Since 1994, OAEC has explored, educated about, and implemented innovative and practical approaches to the pressing environmental and economic challenges of our day.

INTRODUCTION

In the fall of 2008, the WATER Institute of the Occidental Arts and Ecology Center (OAEC) installed a solar hot water system and propane and water monitoring equipment for OAEC’s Guest Bath House. Solar hot water systems are a low-tech and cost-effective way, in both commercial and residential settings, to substantially reduce propane or natural gas consumption for heating water. Approximately 5,000 people come to OAEC each year for sustainability tours, workshops, and events, and this project demonstrates to these visitors a practical way for them to reduce their carbon footprint and save money.

As critical energy supply and infrastructure challenges continue to prevail in California, the state is being called upon to identify and address the points of highest stress and greatest opportunity for change. In 2005, the California Energy Commission issued a report, California’s Water-Energy Relationship, that places the water-energy relationship at the top of the list: “water related energy uses 19% of the state’s electricity, 30% of its natural gas and 88 billion gallons of diesel fuel annually – and the demand is growing.” A report released in April 2007 by Environment California Research & Policy Center showed that a mainstream market for solar water heating could cut 6.8 million tons of global warming pollution per year, while cutting natural gas demand in each home by 50-75%.

The cost of producing energy is skyrocketing as we continue to rely on a diminishing supply of non-renewable fossil fuels to make this energy. The extraction, production, and burning of these fuels impact water, soil, and air quality, adding millions of tons of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere that contribute to global climate change. Couple this with the rise in demand from increasing population pressures, and it becomes increasingly clear that we need to break this damaging cycle. Through conservation and the installation of systems that rely on local, renewable, and sustainable resources, we can reduce the energy and water footprints (the “watergy”) of our human settlements and help preserve the dwindling natural resources that remain.

Taking this dire situation to heart, the California State legislature passed the Solar Water and Heating Efficiency Act of 2007. This legislation is designed to create a broad market for solar water heating technologies by offering $250 million in rebates for the state’s consumers over the next ten years. The rebate fund would come from a $0.13 per month surcharge on gas bills and be implemented by the California Public Utilities Commission and individual municipal utilities. According to the bill’s author, California Assembly member Jared Huffman, (Marin/Sonoma) “California can achieve greater energy independence, fight global warming, and save homeowners and businesses money by encouraging a mainstream market for solar water heating.” (Excerpted from an October 17, 2007 article entitled Solar Hot Water Set To Go Mainstream with California’s AB 1470 by Sara Parker, www.RenewableEnergyAccess.com)

Additionally, with the passage of the Contractual Assessments: Energy Efficiency Improvements Bill (AB 811) in June of 2008, cities and counties in California can now “designate areas within which willing property owners could enter into contractual assessments to finance the installation of distributed renewable energy generation, as well as energy efficiency improvements, that are permanently fixed to the property owner’s residential, commercial, industrial, or other real property. These financing arrangements would allow property owners to finance renewable generation and energy efficiency improvements through low-interest loans that would be repaid as an item on the property owner’s property tax bill. The contractual assessments could not be used to finance the purchase or installation of appliances that are not permanently fixed to the real property.” (Excerpted from Wikipedia). This could provide further financial incentive for homeowners to install solar hot water heating systems.

In April 2009, the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors approved the Sonoma County Energy Independence Program (SCEIP). According to the SCEIP website, www.sonomacountyenergy.org, this program “provides a new opportunity for property owners to finance energy efficiency, water efficiency, and renewable energy improvements through a voluntary assessment. These assessments will be attached to the property, not the owner, and will be paid back through the property tax system over time, making the program not only energy efficient but also affordable.” Solar water heating systems rated by the Solar Rating & Certification Corporation are eligible for funding through this program.

OAEC’s WATER Institute’s response to this water and energy crisis has been to develop and implement an Adaptive Management Plan founded in the principles of Conservation Hydrology. Conservation Hydrology utilizes the disciplines of ecology, population biology, biogeography, economics, anthropology, philosophy, planning, and history to guide community-based watershed literacy, planning, and action. Conservation Hydrology advocates that human development decisions must move from a “dehydration model” to a “rehydration model.” To achieve this goal, we must retrofit existing development patterns and begin implementing techniques that regenerate the watershed and reflect our greater hydrologic responsibility.

Our 80-acre OAEC site employs and demonstrates appropriate technologies and best management and conservation practices for water, and for the energy associated with its use. These practical solutions include: roof water catchment systems, storm water management practices, a rainwater harvesting pond that supplies 100% of our irrigation needs, bio-filtration to improve water quality, and a 10 kilowatt solar photovoltaic system.

By 2008, our demonstration site was still lacking one important solution in this suite of conservation hydrology strategies – a solar hot water heating system. According to the California Energy Commission, “the vast majority of water-related natural gas consumption is by residential, commercial, and industrial consumers, primarily for heating water.” OAEC recognized a key opportunity to demonstrate an important solution that is affordable and has a significant impact on the energy used to heat water. These systems can be used in residential or commercial settings, have a payback period of five to seven years, and are built to last longer than twenty years. As energy prices are projected to increase, this payback period will become even shorter. Installing such a system would support the WATER Institute’s goals of demonstrating viable solutions that meet human needs while minimizing impacts on watersheds and the myriad species that depend on them.

Working with solar designer Matt Every of Integrated Elements, we chose to install a Thermal Drainback System. This type of system is one of the most efficient solar hot water designs and highlights the simplicity of retrofitting an existing structure. We designed it to be broadly applicable and easily replicable by all who might want to install such a system themselves. It supplies solar-heated water to OAEC’s existing Guest Bath House, which is used annually by hundreds of guests, workshop participants, interns, and staff. The Bath House building is strategically located at the center of our site, a place that receives the greatest amount of traffic. Through easily visible roof panels and well-placed signage, we are able to educate the thousands of people who pass through every year. By installing propane and water meters, we are able to demonstrate how to audit one’s “watergy” use and quantify the savings gained by the installation of a solar hot water system.

OAEC WATER INSTITUTE‘S THERMAL DRAINBACK SOLAR HOT WATER HEATING SYSTEM

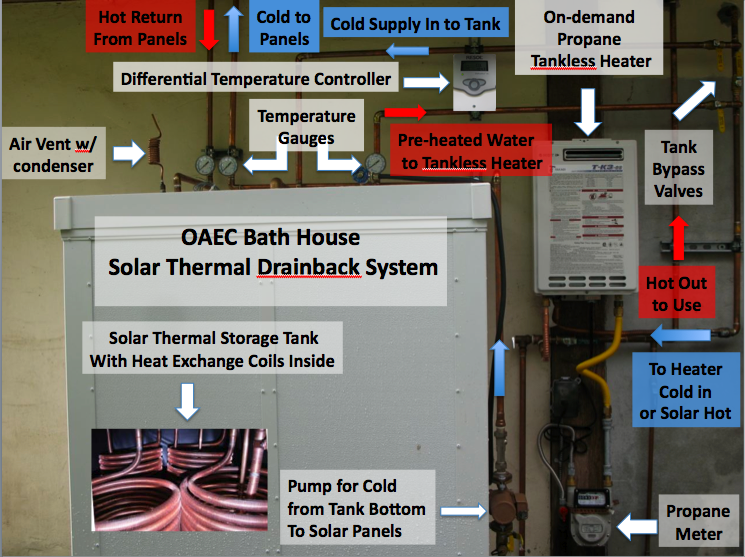

This solar hot water heating system is designed to heat water with the sun using a non-pressurized open loop of plumbing that is not tied into the plumbing of the bathhouse. In this indirect system, roughly 200 gallons of water are pumped from a special solar thermal storage tank (see next photo) to the panels and back to the tank several times a day, getting hotter with each cycle. These panels do not store water to be used directly by users in the bath house as they do in a passive batch system. Instead, they are designed to heat the finite amount of water that gets repeatedly pumped through a storage tank and uses a heat exchanger to heat the actual water to be used in the building. These panels are designed to run the water through as much piping as possible to maximize the amount of time the water is exposed to the heat of the sun. They are placed on a south-facing roof at an angle that ensures the fullest exposure to the sun.

This system is termed “active” because it relies on an electric pump to circulate the water (see next photo). This pump is run by a special monitoring device called a differential temperature controller. This controller monitors the temperature at the thermal panels and at the storage tank. It compares these two temperatures and signals the pump to begin pumping through the panels if there is a great enough differential in temperature for heat to be gained. The water temperature in the storage tank starts at 80 degrees Fahrenheit and during daylight hours increases in temperature with each pass through the panels. When the temperature controller senses there is no longer heat to be gained in the panels, it stops the pumping and the water drains back into the storage tank, hence the name “thermal drainback.” This is how the system protects itself from freezing. As the air temperature goes down, the panels drain and no longer hold water that could freeze and burst the pipes. The panel to storage tank loop is plumbed so that the unpressurized water can drain back into the storage tank using gravity alone.

This custom-made solar thermal storage tank is where the heat exchange happens (the big white box in the left side of this photo). This super insulated tank holds the 200 gallons of water that gets heated by the panels. The cold water that comes in from the supply line to the building is plumbed to enter the storage tank and circulate through 50 feet of copper coil that sits inside and is surrounded by the 200 gallons of solar heated water. Any heat that the storage tank water is holding is transferred to the cold water passing through the coil. This internal heat exchanger makes this system one of the more efficient of its kind.

The preheated water then travels to the propane fueled on demand, or tankless, water heater. This tankless heater is special in that is has an electronic sensor that monitors the temperature of the incoming water and heats it as needed to the desired temperature. If the water that enters is warm enough, it passes straight through the heater without using any propane. This tankless heater has an electrical igniter instead of a pilot light and a fan that blows air across its heat exchanger both of which maximize its efficiency.

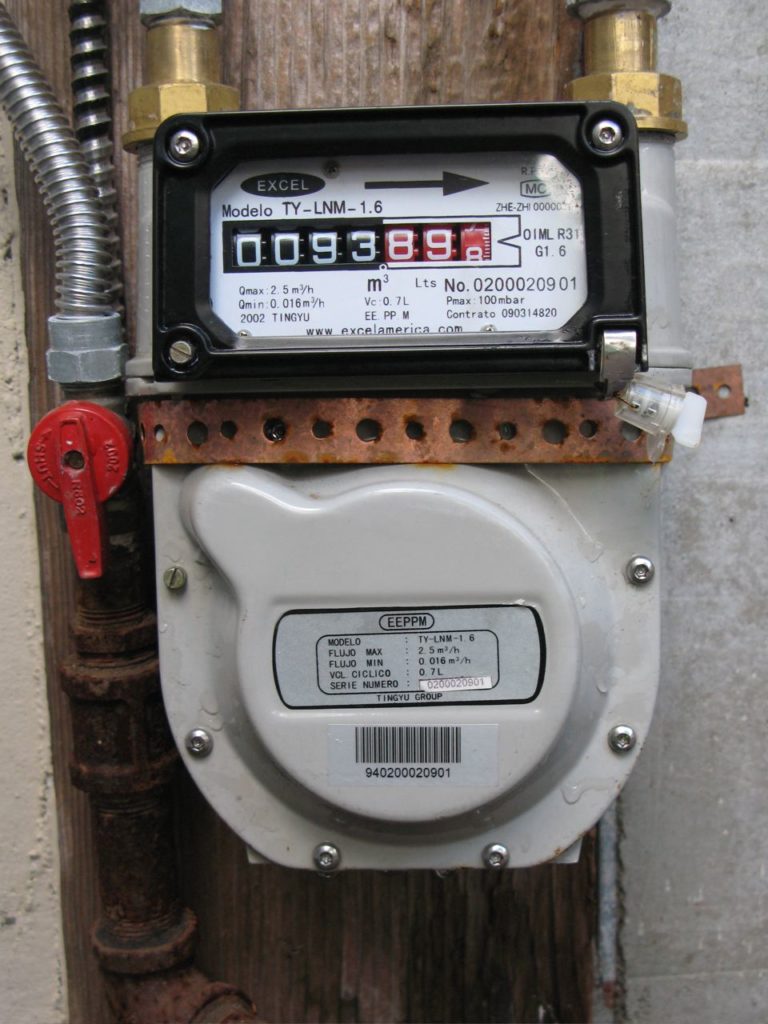

This propane meter allows us to quantify how much gas we are using to heat our hot water. We installed this and collected use data before we switched from a tank to a tankless water heater and then before we installed the solar hot water system. As of this writing, we have been able to record the following data and are impressed with the increase in efficiency of the system and the decrease in propane use (about 1/3 of the amount of gas we were using prior to the installation):

- Using the tank heater with no solar system, we averaged 0.615 gallons per day over a period of 98 days.

- Once we installed the tankless heater, we averaged 0.306 gallons per day over a period of 103 days.

- After installing the solar heating system, we averaged 0.180 gallons per day over a period of 42 days.NOTE: This meter measures in cubic meters so one must convert the data to gallons (1 gallon of LPG = 1.03 m3 of Propane Gas).