A report back from the Wet Meadows Restoration Workshop

In October 2018, WATER Institute partners NOAA Fisheries (National Oceanic), US Fish and Wildlife Service, US Forest Service, Maidu Summit Consortium, and the Placer Land Trust convened a 4-day workshop called Restoring Wet Meadows, Streams and Floodplains: An Ecological Approach. WATER Institute Directors Kate Lundquist and Brock Dolman were invited to participate, contribute, see presentations, and be in the field at two sites that are important to beaver restorations.

Doty Ravine

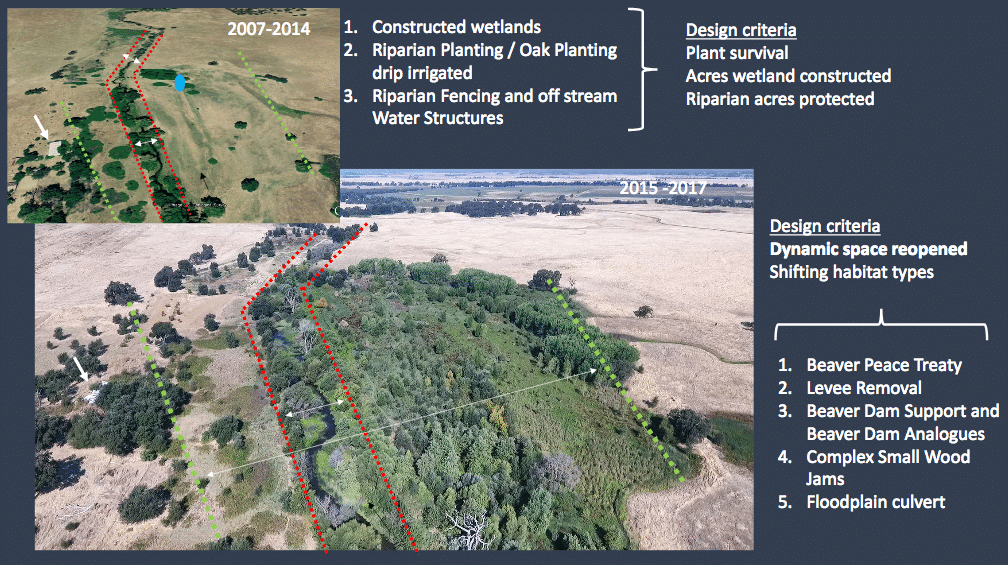

Owned by Placer Land Trust (PLT), Doty Ravine has undergone a huge transformation over the last 5 years. With the help of US Fish and Wildlife Service, they have designed and implemented a plan to reconnect the creek with the floodplains. A key component of this project has been to stop trapping and killing beaver that were already there. Rather than seeing the beaver as the enemy of restoration (they do enjoy eating new tree plantings!), they realized that they could harness the beavers’ engineering prowess to restore this once very dry, limited channel.

Rather than focusing on just the stream, there was an opportunity to restore the entire channel, floodplain, and riparian corridor. They instituted the “beaver peace treaty” for no more lethal trapping. They also removed some cement levies, reinforced existing beaver dams so that they would not blow out in high flows, added other small woody instream features to trap sediment, In doing these small things over the course of several years, Doty Ravine has been transformed from a small, green strip that flowed across a heavily-grazed dry foothill oak savanna, to a lush wetland full of water and dozens of species that also benefit from this newly expanded habitat.

Slide by Damion Ciotti of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Workshop on Ecological Restoration of Streams, Floodplains, and Meadows

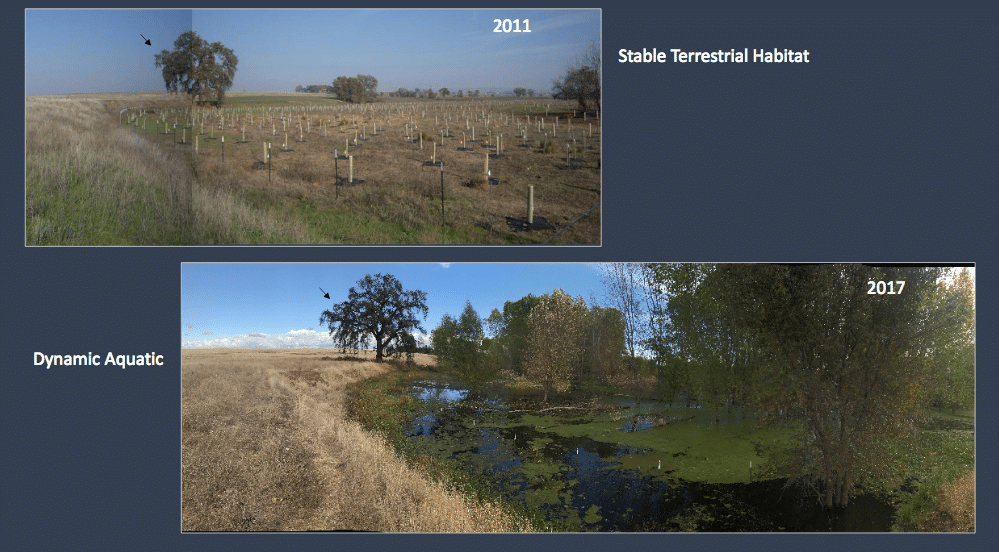

In Damion’s slide below, you can see the original restoration plan, which included an initial planting of oaks along the flood plain, an inappropriate choice for a wetland anyway. After the “beaver peace treaty,” beavers chomped those down. Six years later, the floodplain has expanded significantly, and the oaks have now been replaced by cottonwood, a native tree in the foothills region along riparian corridors.

Slide by Damion Ciotti of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Workshop on Ecological Restoration of Streams, Floodplains, and Meadows

The aerial before and after photos are impressive in and of themselves. But for Kate and Brock, to put on the waders and experience the lushness and diversity of plants and wildlife was an affirmation of the beaver restoration strategy that they have been advocating for for over 10 years.

Doty Ravine is one of California’s best examples of how to integrate beaver stewardship into riparian restoration. It is part of an emerging approach called Process-Based Restoration that embraces and works with dynamic processes such as flows, sediment transport, and the engineering work that beaver are already doing. There is nowhere in California where we have such light-handed techniques resulting in such dramatic results in such little time. It was in part because of the willingness of the landowner (PLT) to embrace these new techniques and the vision of the US Fish and Wildlife Service to design and implement this process-based restoration.

While Doty Ravine is not open to the public, PLT offers bird walks occasionally – contact Placer Land Trust.

Tásman Koyóm

The second site we visited, Tásmam Koyóm, is located in Plumas County and is a maintained meadow at 4,500 feet, sacred to the Mountain Maidu in Maidu territory. Most recently, this 2,300-acre parcel was owned by PG&E, but is in the process of being transferred back to the tribal community.

Read the High Country News article about the transfer.

Mismanagement, including road impacts on the valley, water flow issues, and overgrazing, has contributed to eroded stream channels and other consequences to plant and animal habitat.

The Maidu are very interested in restoring the valley using beaver and Traditional Ecological Knowledge, including stewarding willows for traditional basketry. The WATER Institute has been in conversation with the Maidu Consortium about the beaver stewardship component of their restoration plan and looks forward to future collaboration.

Beaver restoration is happening in CA!

A lot of important folks who attended are actively doing restoration for agencies in the state and want to begin process-based restoration, including beaver restoration. The opportunity to get chest deep in a beaver bog with other wildlife biologists, plant specialists, hydrologists, climatologists, landowners, and agency professionals was an important collaborative moment for the #beaverbeliever movement!

In part due to the WATER institute’s decade campaign to promote beaver, we are excited to see this level of interest amongst agencies and restoration practitioners. Doty is a great case study that we can all be learning from. For those of us who don’t have beaver in our immediate area, the WATER institute continues to work on changing beaver policy so that one day we can rewild beaver to their native range.