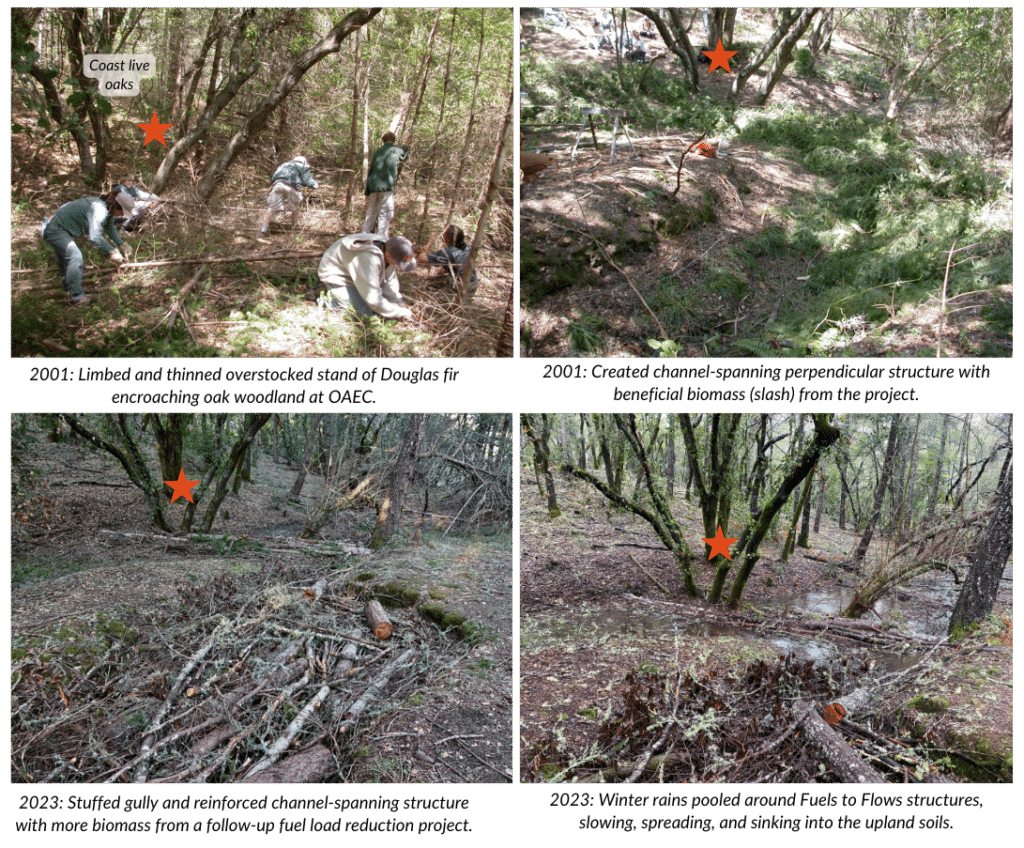

Gullies are seasonal drainages that only flow during rain events. They actively erode, delivering sediment pollution downstream and reducing the water holding capacity of upland landscapes. The formation and deepening of gullies dehydrates the soil sponge, creating a negative feedback loop of drought, forest stress, and worsening wildfires.

Gully stuffing is a process-based restoration technique that utilizes natural materials to stop erosion, improve soil health, and promote water infiltration. This practice is similar to “brush plugs” or “brush check dams” and strategically packs limbs, leaves and other organic materials into the channel to slow, spread and sink water. Gully stuffing is one option in the Beneficial Biomass Portfolio and is part of a holistic response to the major question in vegetation management and fuel load reduction work: what to do with the leftover biomass?

First, watch this animated introduction to the practice of gully stuffing for a general overview. Then watch the more in-depth, step-by-step How to Stuff a Gully video in the How To section of this page (scroll down).

Benefits

Gully stuffing puts the by-product of vegetation management to good use rather than hauling it away, burning it, etc. It can save time, energy, and money by using on-site materials for watershed restoration rather than importing or purchasing materials from elsewhere. Gully stuffing benefits watersheds and upland ecosystems in the following ways:

Sediment is one of the primary pollutants in our watersheds. The dense matrix of a stuffed gully can decrease the erosive power of water while trapping and filtering sediment. This reduces sediment delivery downstream, benefitting salmonid habitat and aquatic life.

Gullies dewater the upland landscape. They carry surface water away quickly, rather than allowing it to soak into the soil sponge. Gullies also drain the shallow water table of the surrounding area. The water table can only recharge up to the lowest point in the gully, like a bathtub only filling up to its overflow drain. Stopping or slowing the downcutting of gullies and rebuilding them back up may increase water storage in the soil and water flow later in the dry season.

The active point of erosion in a gully is referred to as the “headcut” or “knickpoint,” a sharp change in elevation that creates a scouring waterfall during high flow. Without treatment, headcuts “migrate” or move upstream as the gully deepens and widens. Interrupting or reversing this migration is key to stopping erosion and can keep roads and trails passable.

Stuffing gullies create cool, moist habitats, as well as small pools that remain wet further into the dry season, benefitting a multitude of semi-aquatic species. For example, here at OAEC, we have observed ensatina, arboreal, black, lungless, and California slender salamanders as well as rough-skinned newts. These pools also provide an extended source of drinking water to mammals, birds and other wildlife. Latent flow and filtration caused by the dense matrix of a stuffed gully also provide cleaner, colder, more copious water for salmon and other fish downstream.

A stuffed gully is essentially a compost pile that breaks down over time and stores carbon long term. This compost provides a moist, nutrient-rich root bed for plants to grow into, improving the resiliency of the trees that remain after a thinning project.

Storing carbon on site avoids the greenhouse gas emissions caused by hauling material away or burning it via wildfire or pile burning. While some of these other methods of “disposal” may be the most applicable solution in certain situations, gully stuffing is another tool in the toolbox for balancing the carbon budget of your restoration project.

Is gully stuffing right for my situation?

The gully stuffing practices described here are for upland ephemeral or seasonal gullies (known in hydrology as “first-order streams” and in the California Forest Practice Rules as “Class III streams”), that is, streams that do not support aquatic life and only flow during or shortly after rain events. Stuffing techniques in other stream orders require other design and permitting considerations.

Ideally, the gully is near a defensible space or vegetation management project so that the resulting biomass from these projects can be efficiently utilized as your primary stuffing material. This may be an overstocked forest, shrubland or meadow.

PLEASE NOTE: Vegetation management and defensible space work has its own set of best practices, site assessment criteria, and permitting and timing considerations (including nesting bird surveys) not covered here. For more information on vegetative management in Sonoma County, visit the online resource guide Tending the Land.

While erosion and sedimentation are natural processes, the conditions that have created the vast majority of gullies stem from increased runoff from upland land uses, such as road building, logging, overgrazing, industrial agriculture, and urbanization. Identify and address root causes of erosion upstream and downstream whenever possible for example, unclog a culvert, reduce impervious surfaces, or regrade a road. Taking stock of and designing solutions for source problems is key to restoring your site.

It is critical that you understand where your project site sits within the larger drainage network and how water flows through the landscape. What watershed are you in? Where does the water that flows through your site come from and where does it go? (View this GIS watershed map of Sonoma County) Observe your site and the surrounding area in both dry and wet conditions. Keep in mind that certain interventions may or may not be appropriate in the context of your bioregion and the solar aspect of your site. For example, a hot south-facing slope in the desert might call for a different treatment than a north-facing redwood grove on a foggy coast.

A historical understanding of the energy, scale, and force of the water entering your project site throughout the year is essential to designing a successfully scaled project. During the heaviest rain events, how much water flows through your site? Read the topography, consider the drainage area, and study the underlying soils. The volume of water and the steepness of the channel are the two primary factors that determine the energy of flow, also known as “stream power.” In general, plan to scale your project to accommodate the increasing variability and extremes of climate change.

Carefully observe and survey all of the plants, animals, and other living features within your project site before designing and again before beginning the actual work to avoid any unintended consequences and to maximize benefit to resident species. The presence of endangered and/or threatened species requires an increased level of attention and professional consultation.

Gully stuffing techniques are increasingly being applied across a wide diversity of landscapes; however, they have not been peer reviewed. Consult with professional restoration ecologists, conservation hydrologists and regenerative foresters to help inform your restoration plan. The California Process-Based Restoration Network (CalPBR) is a wonderful hub of resources and training opportunities to expand your knowledge or find professional help.

Note: OAEC does not have the staff capacity to answer inquiries about gully stuffing and does not offer consultations to individuals about permitting, site assessment or implementation. Please visit the CalPBR website to connect with a professional.

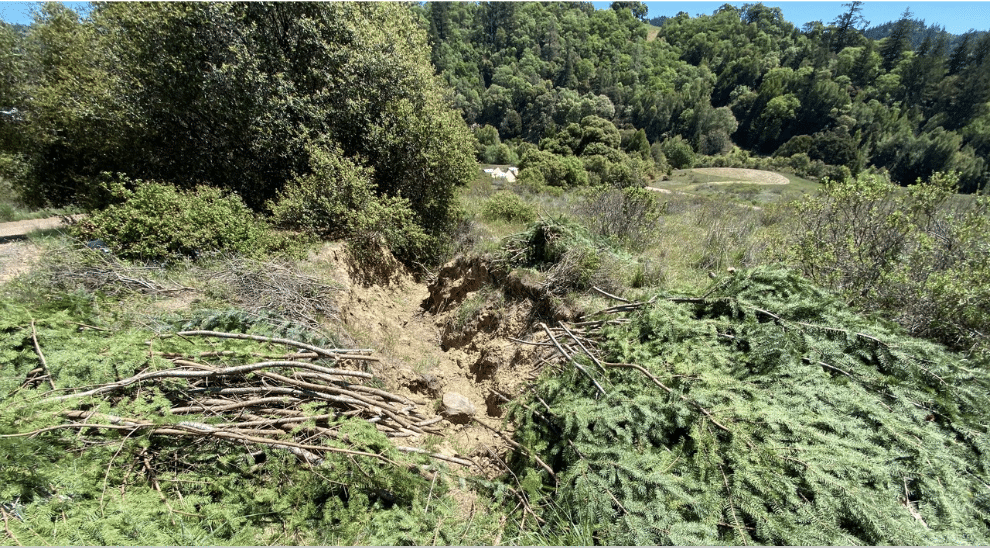

Shown above is a deeply incised gully in a forested upland scenario that might be a good candidate for stuffing. This is a seasonal drainage that only flows when it rains (not fish habitat) and is close to potential forest thinning and limbing projects. Check with your local water resources agency to determine if permitting is required. Photo: Sashwa Burrous

Permitting

Gully stuffing requires a consultation with the appropriate agencies to determine whether or not a permit is needed. Currently in California, gully stuffing in ephemeral, non-fish bearing upland channels (known as first-order streams in hydrology or defined as Class III streams in the California Forest Practice Rules) requires consultation with state agencies, such as your Regional Water Board and the California Department of Fish & Wildlife. You should check with your regional and state agency representatives to determine if you need a federal consultation as well. Stuffing gullies in other stream orders require other design and permitting considerations.

In 2021, when OAEC initiated a series of gully stuffing pilot projects in first-order/Class III streams, the consultation and permitting process included the following:

- Submitting a “Notice of Intent” to the North Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board, along with pre-project photos and maps. Upon review, the Board issued a “Notice of Applicability” (NOA).

- Acquiring a Lake and Streambed Alteration Agreement (LSAA) through the California Department of Fish & Wildlife.

- Consulting the Army Corps of Engineers. It was determined that we did not need a federal permit.

However, in the years since OAEC first obtained these permits, there has been much progress toward reducing permitting barriers and increasing agency support of these high-reward, low-risk techniques. Read more about our Fuels to Flows Change the Rules Campaign.

Check out Sustainable Conservation’s Accelerating Restoration database to get oriented to the regulations in your area.

Above, OAEC led a process-based restoration (PBR) workshop with Tribal EcoRestoration Alliance (TERA) and Robinson Rancheria Pomo Indians of California. We stuffed several sections of a gully just downhill from the 151 acres that were burned in the July 2024 Acorn fire. The goal was to capture toxic ash and sediment and prevent it from polluting a pond downhill where Clear Lake hitch, an endangered species, are being raised. Photo: OAEC/Brock Dolman

Timing Considerations

Currently, gully stuffing requires a consultation with local agencies, which is a major timing consideration. Your agencies will let you know if a permit is needed. They will also consider seasonal flow and other sensitive ecological factors to determine when you can and cannot work in these Order I/Class III drainages. A good rule of thumb is to get in touch with regulators early, as it may take some time to get permits processed before you can begin your project (see above).

Gully stuffing is best done in coordination with or shortly after your vegetation management or defensible space project generates the stuffing material. In California, most vegetation management typically happens in late summer and early fall, with particular timing considerations around nesting birds not discussed here.

For best results, stuff your gully just before the “first flush” of winter rain. The reason for this timing is three-fold:

- Don’t miss the opportunity to put the stuffing material to good use before it dries out! Using the slash right away ensures that the material is green and flexible. There is great benefit if the finer leaves and needles haven’t broken down and maintain their filtration capacity when the first flows arrive in late fall or early winter.

- The first significant rain of the season is disproportionately rich in fine sediment and organic matter that we want to capture. This is especially true after a fire, logging, or major earthworks project (such as road grading or development) upstream from where you are working.

- When rains do come, the unwetted stuffed material in the gully will get saturated with water. Doing this work as close as possible to the first rains shrinks the window of fire vulnerability and the risk that this material could ignite.

Resilience Works and North Bay Jobs with Justice stuff a gully at Monte Rio Redwoods Regional Park to mitigate the impact of a problematic road culvert that was causing significant erosion. Photo: OAEC/Brock Dolman

How to Stuff a Gully

Once you have completed a site assessment and design and obtained any needed permits, these are the steps to stuff a gully:

Gully stuffing can consume a significant amount of leftover biomass from your vegetation management project. As you work, process and sort your material into piles of similar sizes and types, such as: 1) green, flexible coniferous boughs like Douglas fir or coastal redwood; 2) less uniform branches and limbs of hardwood species like California bay and tan oak; and 3) larger trunks and woody material. Pile your material with the tips all facing the same direction.

Freshly limbed conifer boughs (aka “green gauze”) staged with cut ends conveniently facing the gully and ready to be laid in as the primary base layer. Photo: Brock Dolman/OAEC.

The green conifer boughs will be used first, so stage these bundles closest to the gully, with the cut ends facing the gully. Depending on the scale of your project, it may be helpful to have a few people working down inside the gully with others processing and feeding them material.

Clear out any debris, such as leaf litter and fallen branches, as you will want a clean seal between the first layer of gully stuffing material and the base of the channel. Save this material to be reincorporated later.

Starting just below the headcut (the active point of erosion at the top of the gully), begin placing the first layer of fine green material or “green gauze.” The cut ends should face downhill with the tips pointing upstream (the opposite of laying roof shingles, as you are trying to slow the flow). The goal of this first layer is to cover the entire bed of the gully or anywhere there is exposed channel bed with a solid 4 to 6-inch layer of green gauze. Be attentive to adhering or plastering material against all the edges and sealing up little gaps, holes, hanging roots, and pockets so water doesn’t escape beneath or around your structure and continue to scour out the gully. This layer is the most important to the long-term success of your project.

Begin mixing in other material on top of your green gauze layer to fill up the gully to just a few inches below the lip of the channel. This step can go faster, with less attention to the direction of your material. Compress and compact as you go (chopping with loppers may be helpful), stepping and stomping on the material. At this stage, you can lay in almost any size or type of material: branches, leaves, smaller poles, wood chips, etc., creating a densely packed matrix. Be sure to mix in larger logs, as they provide more durable, longer-lasting structure. You will be surprised how much biomass can be stuffed into a gully!

Important: Check height and maintain U-shape as you near the top. Fill the gully up until it is about 4 inches lower than the lip of the headcut or the edge of the bank. It is also critical that the finished shape of your material forms a U-shape (lower in the middle, higher on the sides when looking up the gully) to properly guide water during rain events and ensure that the first flush deposits sediment and debris on top of your packing material. Overstuffing your gully may push water out of the channel onto the adjacent slopes and cause erosion.

This will help prevent unintended mobilization during rain events. As the larger logs break down more slowly, they also provide a longer-lasting mycorrhizal root bed for the trees.

Variations

The following variations may or may not be appropriate to your situation.

If your gully has a higher stream power (steeper slope, more flow), you may need to pin the structure in place with wooden stakes to keep it from loosening and being swept away downstream. Stakes are also useful when working with brush that is difficult to compress. If you are unsure, it is best to add stakes to your project.

Stakes can be made easily with wood from your on-site project (redwood limbs, for example, are durable and rot-resistant). Stakes can be pounded in at strategic points at an angle to create a chevron or an X that anchors the structure and prevents it both from rising up vertically or sliding downhill.

To further slow the flow of water, you may choose to install perpendicular wood “weirs” that act as small “speed bumps.” These perform a similar function to what are known as “trench plugs” in utility trenches. After the initial green gauze, lay in a series of larger limbs or trunks across the width of and perpendicular to the channel, as shown below. Once installed, continue filling with material to cover.

If you are worried about mobilization, you may choose to first dig and secure the logs in a shallow trench in the base and sides of the channel before the green gauze layer, shown below.

Where the gully has a flatter slope, greater width, or the possibility to reconnect to accessible floodplains, you have a good opportunity to install a structure or a series of structures that run perpendicular to the gully in a half-moon shape to further slow the flow and improve infiltration of water into a larger area of soil.

If you identify natural pools along your gully where water remains into the dry season, such as the seasonal pool below, you may choose to maintain them rather than filling them in, to encourage a water source for wildlife drinking or newt-breeding pools.

Observation and Adaptation

Gully stuffing is not a one-and-done solution, so expect to revisit and adaptively manage over multiple seasons. A premise of process-based restoration is that these structures are meant to become incorporated into ecosystems that are dynamic and ever-changing. Maintenance is not failure.

During and after flow events, visit your project to verify that the material you installed is functioning properly. If water is scouring out around or beneath the material, or if significant pieces of wood or volumes of soil are moving, then maintenance is needed. Observe how water moves through the stuffed gully and repair or rebuild as necessary.

Over time, the material in the gully will break down like a compost pile and settle. You will likely need to add more material to bring up the elevation of the stuffed gully or reinforce specific areas, like the headcut, with extra bundles of green gauze. Within a matter of years, if tended to properly, the organic matter will become a stable root bed that requires little to no maintenance.

Note: OAEC does not have the staff capacity to answer inquiries about gully stuffing and does not offer consultations to individuals about permitting, site assessment or implementation. Please visit the CalPBR website to get connected with a professional.